Welcome to the world of fungi!

Studying fungi

The Greek name for fungus is myco (or myko), so the study of fungi is mycology. A person who studies fungi is a mycologist.

What are fungi?

Fungi are in their own kingdom, seperate from animals, plants and other organisms. Fungi are eukaryotes. So, as with other eukaryotes they have their DNA enclosed within a membrane-bound compartment or nucleus. They also have membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria, plastids, vacuoles and an endoplasmic reticulum.

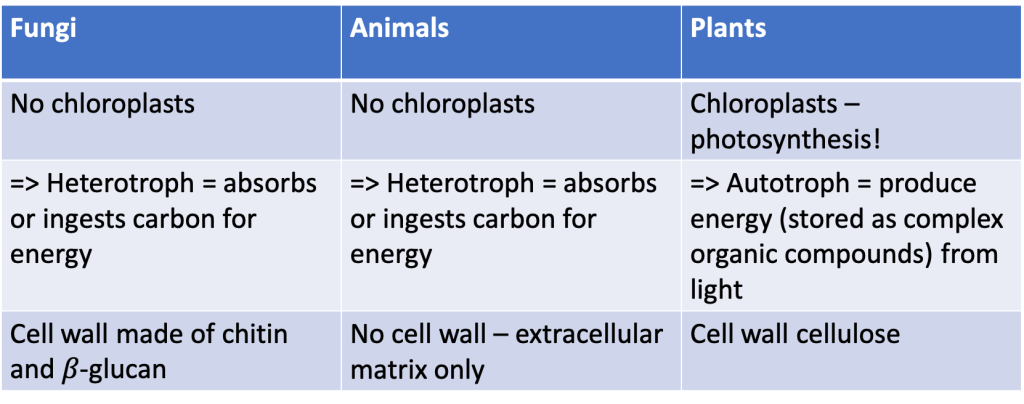

How are fungi different from plants and animals?

There are a number of differences between animals, fungi and plants. Fungi and animals don’t have chloroplasts or chlorophyll, so they can’t photosynthesise. Both fungi and animals are heterotrophs. They absorb or ingest carbon for energy whereas plants are autotrophs. They produce energy from light. Both fungi and plants have a cell wall. Animals have only an extracellular matrix. However fungal cell walls have a different structure to those of plants and are made of chitin and 𝛽-glucan rather than cellulose.

Fungal growth

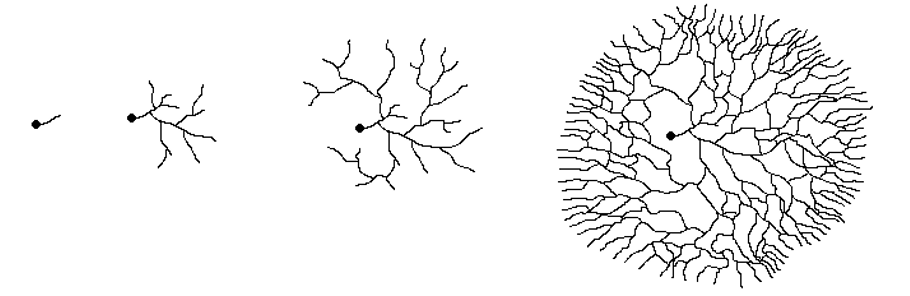

Most fungi reproduce and disperse using spores. A spore will land somewhere and if the conditions are right it will germinate, producing a germ tube which grows into hyphae. The hyphae continue to grow. Collectively a mass of hyphae like this is called a mycelium.

A mycelium will continue to grow while there is adequate nutrition and water. They have indefinite growth.

As a great example of this, there is a particular fungal individual called the humongous fungus living quite comfortably in the soil of a forest in Oregon in the US. It’s 3.8km wide and covers over 2000 acres. It is actually a tree pathogen in the genus /Armillaria/. It is between 2400 and 8650 years old.

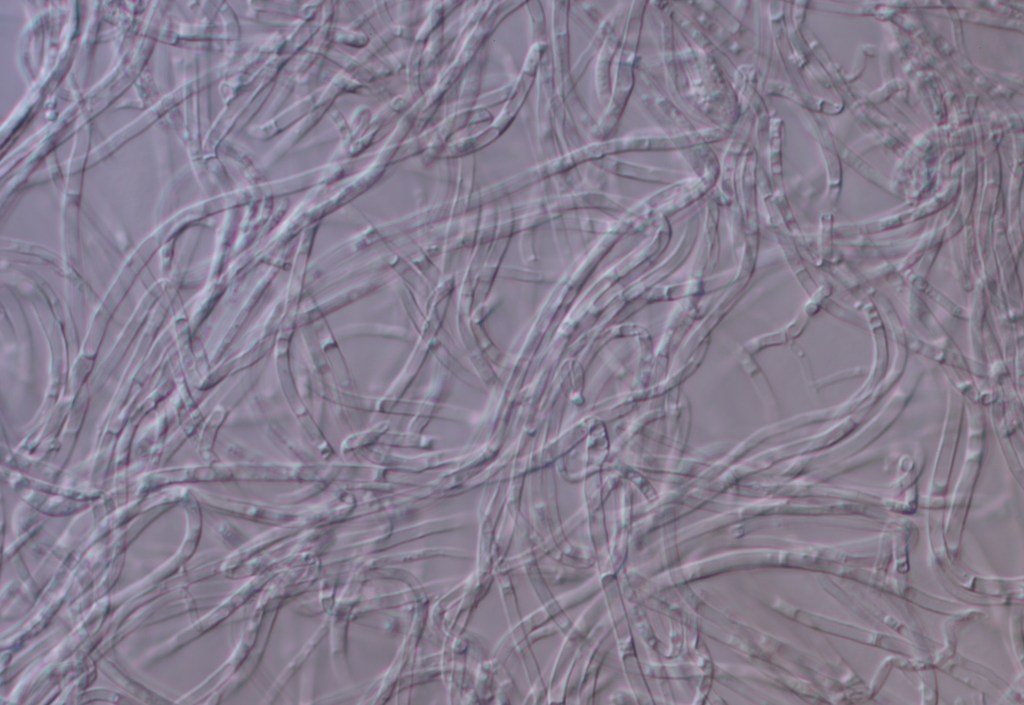

Hyphae are microscopic tubes of cytoplasm bounded by tough, waterproof cell walls, except at their tips. Hyphae is the plural. Hypha is the singular. Fungi that grow as hyphae are called filamentous fungi (some fungi grow as yeasts – more on this later). Hyphae are usually about 2 𝜇 m wide, but this can vary. They can be pigmented, but are mostly transparent, or ‘hyaline’. They can be septate or aseptate.

If you have ever been digging around in the garden, or turned over a log in a forest, chances are that you have seen these white filaments. This is fungal mycelium.

External digestion

Fungi get energy and nutrition through external digestion. The hyphal tips secrete enzymes into the substrate. Enzymes break down the substrate (organic molecules) outside of the fungal cells. Hyphae then take up the smaller, more easily absorbed molecules. A really important point here is that fungi therefore need a moist environment in which to secrete enzymes and for those enzymes to act. If there is no moisture, then fungi can’t grow (usually).

Yeasts

Most fungi are filamentous, but some grow as yeasts. These are mostly unicellular and reproduce by budding. Some fungi can switch between hyphal growth and yeasts. These are called dimorphic fungi. “Yeast” refers to a morphotype, a way of growing, not a phylogenetic group. They are used in making beer, wine and bread.

Where do fungi grow?

Fungi grow anywhere that there is enough moisture and energy. They are prolific in soil and serve an essential role in most ecosystems in breaking down dead organic matter. They colonise and decompose wood, dead leaves, dead animals and herbivore dung. They grow in and on living plants – in their leaves, roots and stems. They are in the intestines of most vertebrates and some invertebrates. They are in marine ecosystems. There has been a proliferation of papers in the last 10 years reporting fungi growing around deep sea vents and also in other places in the deep sea. They thrive in freshwater ecosystems and have even been found in groundwater.

They live from the polar regions through to the tropics.

Fungal reproduction

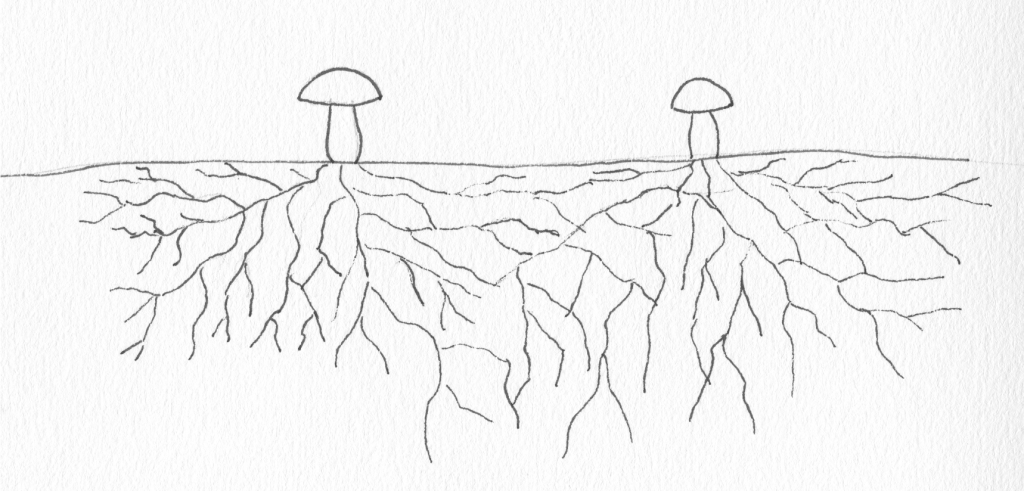

When you walk through a forest, if you are lucky, you might see a toadstool or mushroom. The one and only function of mushrooms and toadstools and other types of fruit bodies is reproduction. So if you’re walking through a forest and you see a nice pretty fungus on the ground, what you’re looking at is its reproductive structure. All the activity, growth, and decomposition is happening in the soil under your feet. Some fungi will only produce fruit bodies every few years, some produce them every year around the same time, some will only appear after fire. The production of fruit bodies can be really variable, but the hyphae, or mycelium, is always there. In the soil. In the wood. In the leaves. Almost everywhere.

This is a more realistic impression of fungi. Beneath the soil there is a network of hyphae busily decomposing fallen leaves, branches, dead insects and other dead organic matter. On the surface of the soil there are fruit bodies for the dispersal of spores.

Fungal reproduction can be complex. There can be multiple mating types. Unlike animals with just 2 sexes, fungi can have multiple. Some fungi can undergo sexual reproduction with themselves. Others have 2 or more mating types.

Many fungi have both sexual and asexual reproduction. The results of sexual reproduction is meiospores. The results of asexual reproduction is mitospores (= conidia). Some have lost the ability for sexual reproduction or vice versa. The sexual and asexual structures will look quite different to each other.

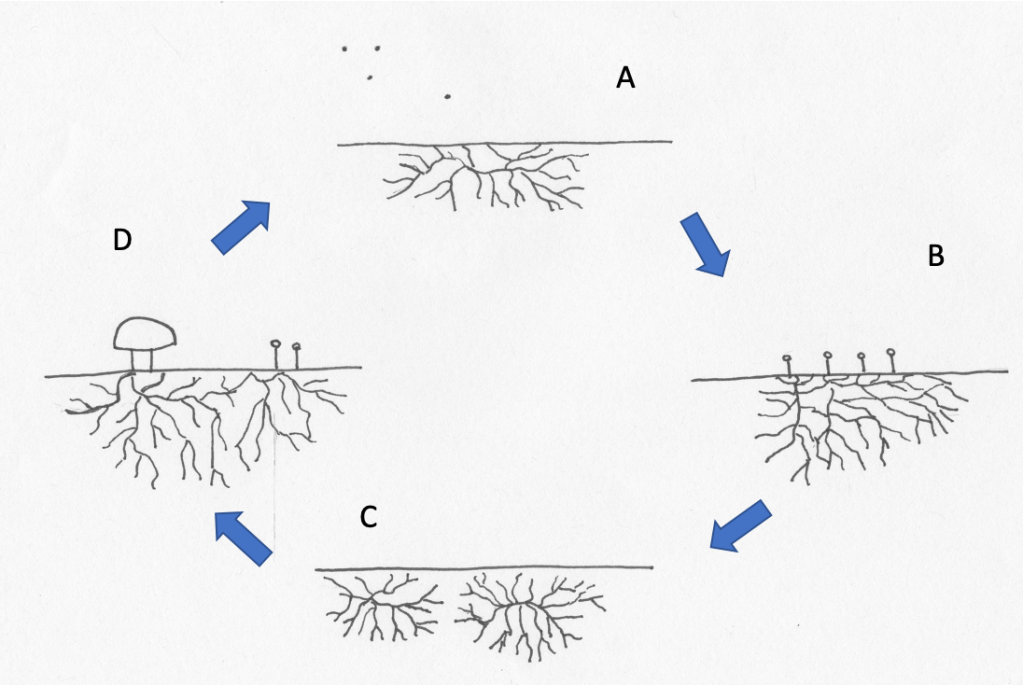

A highly simplified diagram of a fungal lifecycle

A – Spores land on a substrate. If conditions are right, they germinate and hyphae grow. B – If conditions are right, then asexual reproductive structures can grow and release conidia. C – Two compatible individuals of the same species meet and exchange nuclei. They form one mycelium. D – The new mycelium can produce sexual and/or asexual reproductive structures and release spores and/or conidia. **Note – there are many variations on this lifecycle

This is a highly simplified diagram of a fungal lifecycle. If you start at the top at A you can see some hyphae happily growing in a substrate. The substrate could be soil, wood, leaves, or whatever. It can produce some asexual fruiting bodies like those in B and produce conidia by undergoing mitosis. It can keep growing like this indefinitely until it runs out of nutrients. At some stage it might come in contact with another fungus of the same species. If they have compatible mating types, then they’ll fuse together, giving each other a copy of their nuclei and carry on growing. When the time is right this new mycelium might decide to undergo some sexual reproduction. It already has the two parent nuclei within its cells. It just forms a sexual fruiting body, like a mushroom, undergoes meiosis and releases it sexual spores. This same mycelium may also be able to produce asexual structures and release conidia.